About seven years ago I was directing a production the The Winter’s Tale. One day it occurred to me that Perdita’s story was structurally similar to the stories of Snow White and other fairytale princesses. And, of course, the other heroines of Shakespeare’s romances followed this structure, as well. Before I knew it, I was investigating the link. I became drawn to the princess fairytales as keenly as I am drawn to the great mythologies of the world.

I found what I call “the lost daughter” to be a common archetype in story telling. And I found that the fairytale versions of this story delve much deeper than the reductive coming-of-age or sexual awakening themes that are typically assigned to them in college classrooms. The lost daughter is a symbol of humanity’s deepest angst in the face of existence and mortality. She is lost innocence, yes, but more importantly, she is lost youth and beauty. She is the morning, her companion is time, and she walks steadily into the arms of night. In fairytales her name is Aurora, Cinderella, Snow White, Rapunzel, and others. In Shakespeare her name is Marina, Imogen, Miranda, the tragic Cordelia, and of course Perdita (literally meaning “lost girl”).

A few years after that production of The Winter’s Tale, I decided to write my own stage version of Snow White. When I put it on its feet, I was surprised by how well it was received. People really love these stories. So then, this past summer, I decided to write another one: Sleeping Beauty. But it’s hard to write a play wherein the heroine spends much of her time sleeping. That’s when I started wondering about Aurora’s dreams.

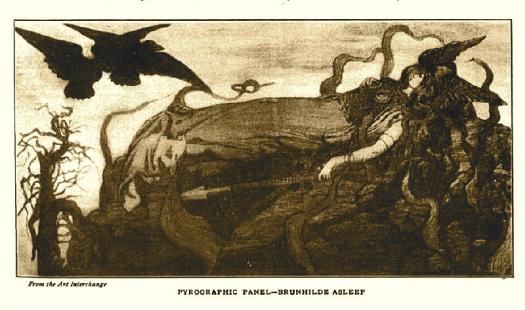

One of the many versions of the Sleeping Beauty story is the story of Brynhildr (or Brunhilde). Brynhildr was a valkyrie cursed to sleep by the god Odin. Valkyries chose who lived or died on the battlefield, and Odin became angry when Brynhildr chose an outcome against his wishes. He cursed her to sleep in a ring of fire, there to remain until the ring was broken. Wouldn’t it be interesting, I wondered, if Brynhildr dreamed Aurora’s story and Aurora dreamed Brynhildr’s story?

The various parts came together quickly. I was already marrying Norse mythology and a western European fairytale, so I had no trouble adding Greek and Irish mythologies to the mix. The story of the mythological Aurora and her lovers Tithonos and Kephalos fit nicely with Sleeping Beauty’s century of sleep. And Tithonos’ choice in my version is similar to the Irish story of Emer and the hero Cuchulain. My three good witches are the primordial Greek goddesses of night, time, and youth (Nyx, Ananke, and Hebe), so their powers are actually functional to the story. (And two of the three have really interesting daughters in a story about daughters.)

The fourth witch, the evil one famously named Maleficent in the Disney version, is taken from Shakespeare. The witch Sycorax, mother of Caliban, never actually appears in The Tempest, but she is nevertheless an important figure. I didn’t want to just use her name. I thought it would be more interesting if the witch from The Tempest and my witch were one and the same. I have wanted to write about Sycorax for some time, and this play seemed like a good place to start. Nobody knows how Shakespeare came up with her name, but the best guesses are all from Greek (my favorite meaning “breaker of hearts”). So it’s not a huge stretch to make Sycorax, the witch of darkness, the daughter of the Greek goddess of night.

And that was it. Suddenly I had a new version of the fairytale that combined Aurora’s and Brynhildr’s stories. Once again, I was surprised and gratified by how well it was received. Both of my princess fairytales have been performed at the school where I teach, but they were written for adults to perform for children. I look forward to producing one of them with Sting & Honey.

People can get snooty about fairytales. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard complaints about the Disney versions, with claims that the Grimm versions are the “real” ones. That is ignorant nonsense. I guarantee you that when people read the Grimm versions there were complaints about them being watered-down corporate rubbish. These stories have been told and retold for centuries. They are nobody’s property, and nobody has ever told them the “right” way. That’s part of their beauty and their staying power. And, for the record, Disney’s Sleeping Beauty is an exquisite film.

One more thing: As a result of western culture becoming more politically puritanical, there is an ongoing attempt to phase out these stories. But the more we try to silence old stories because elements of them fail to live up to some transient sociopolitical standard, the stupider we become. I have touched on this before regarding The Odyssey. Such prudery is anti-intellectual and, frankly, adolescent. You don’t like the stereotypes in Cinderella? Instead of trying to silence the version of the story you don’t like, write your own version. After all, whether you like it or not, the story is about you.

*

HEBE:

Hebe means youth, and so I have no daughters.

In fact, I am the daughter’s living symbol,

Fated to be lost in the woods, on waters,

Or in a dream because I touched a spindle.

And while I’m lost I spend my time with fairies,

Poor shepherds, witches, dwarves, or even wolves.

Lessons are learned: a good girl never varies

In what is true, and knows just whom she loves.

But that is not the poet’s true design––

The lost girl is not truth, but youth and beauty.

It’s youth and beauty all of us resign,

Then fill the void with wisdom out of duty.

But wisdom never satisfies the lack,

And that same girl is never coming back.

–Javen Tanner